Jack Johnson, the Fight of the Century, and Race in America

In 1908, African American prizefighter Jack Johnson took on the reigning world heavyweight champion, Tommy Burns. In front of thousands of spectators in Sydney, Australia, Johnson defeated Burns in 14 rounds, becoming the first Black Heavyweight Champion of the world. Johnson would go on to hold the crown for seven more years, during a time when racial animosity, segregation, and even lynchings were widespread across the United States.

Vox recently aired the last surviving film frame of the Johnson-Burns fight, along with an interview with American University Associate Professor of History Theresa Runstedtler, who provided historical and racial context. Runstedtler is the author of the book Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (University of California Press, 2012). She is a scholar of African American history, and her research examines Black popular culture, with a focus on the intersection of race and sports.

Runstedtler explained that boxing fans at the turn of the twentieth century viewed the sport through the prisms of nationality and race, and they lined up to see Black boxers pitted against white boxers. “They imagined that boxers in the ring, particularly for interracial fights, were almost engaged in this kind of Darwinian struggle,” she said. “Fights between white men and Black men became a kind of metaphor for race relations. So, in other words, if a white man won, it would reinforce ideas of white supremacy. But if a Black man won, then it would upend ideas of white supremacy.”

Burns' defeat at the hands of a Black American fighter disrupted that narrative of white supremacy, says Runstedtler. “Johnson holding on to the heavyweight crown was just not acceptable in an era of white imperialism, Jim Crow, and global white supremacy.” And from the moment Johnson won the crown, white Americans began to search high and low for a "Great White Hope" to defeat him. Two years later, they thought they had found this hope in former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries.

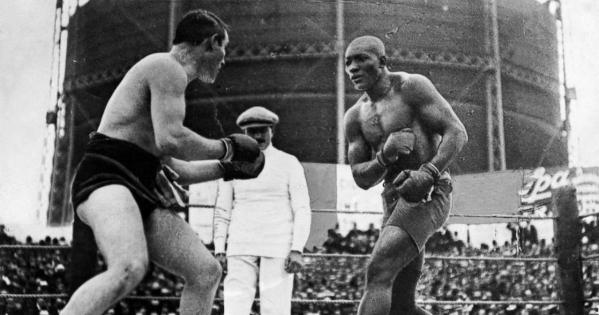

The Fight of the Century

Jeffries came out of retirement to fight Johnson in what was billed as the "Fight of the Century" on July 4, 1910. But it was a fight that did not turn out like many white Americans had hoped. Johnson knocked out Jeffries in the fifteenth round, securing the heavyweight crown again. His victory sparked racial violence across the United States. At least 19 people were killed, and hundreds more were injured — most of them Black

“And they called them race riots, but essentially it was white mob violence against African Americans,” says Runstedtler. “It became this kind of attempt to put African-Americans back in their place.”

Fears of further unrest led to an immediate attempt to ban the Johnson-Jeffries fight film, and in 1912, the US Congress banned the screening of all title fight films entirely. “White authorities were worried about the symbolic implications of the Jack Johnson victory being replayed,” explains Runstedtler. “They worried that any demonstration of Black victory, and any demonstration of white weakness or defeat, would undercut the narratives of white supremacy. Not just in the United States, but in colonies like South Africa, also India, the Philippines.

Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line

Runstedtler first started researching Johnson back in graduate school at Yale University. For her dissertation, she originally focused on Black transnationalism and internationalism, and she was reading a lot of personal correspondence and organizational records. “It just wasn’t riveting to me,” she says. But at the same time, she had just completed a grad school seminar paper on African American boxer Joe Louis, and she presented this research at a conference. One of the panelists suggested that she should do her dissertation on boxing as an interesting way to explore larger issues of race in the early twentieth century.

Intrigued, Runstedtler began to read about African American boxers, including Jack Johnson. “In some ways, he was the first global Black celebrity, traveling all over the world,” she says. Johnson fought against the color line in Sydney, London, Cape Town, Paris, Havana, and Mexico City. His life was a living example how issues of race, gender, and empire played out globally in the early twentieth century.

Runstedtler’s research on Johnson took her to France to do research in the national archives, and to London’s archives and libraries. She also traced his story in American, South African, and Australian headlines and press stories. “Johnson became a figure through which everyday people, boxing fans, and promoters talked through racism and Blackness in the early twentieth century,” she says.

Her dissertation was ultimately published as Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner. The book, which won the 2013 Phillis Wheatley Book Prize from the Northeast Black Studies Association, was released to glowing reviews from academics and sports media alike. Boxing News wrote, “This book is a must-have addition to any boxing fan's library.” David Levering Lewis, author of W. E. B. Du Bois, 1868-1919: Biography of a Race, wrote, "Theresa Runstedtler traces Jack Johnson’s fabulous, furious, iconic life across five continents and through four paradigms (race, masculinity, imperialism, and popular culture), setting a formidably high bar in the emerging genre of transnational biography. Jack Johnson: Rebel Sojourner is a groundbreaking achievement.”

At AU and Beyond

Runstedtler has published scholarly work in the Radical History Review, the Journal of World History, American Studies, the Journal of American Ethnic History, the Journal of Sport and Social Issues, and the Journal of Women’s History, and book chapters in Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem, and In the Game: Race, Identity, and Sports in the Twentieth Century.

She won a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar Fellowship to work on her second book, currently in progress and tentatively titled Black Ball: The ABA, the Slam Dunk, and the Struggle for the Soul of Basketball in the 1970s (under contract with BoldType Books, Hachette). It examines how Black players transformed the professional hoops game, both on and off the court.

“Theresa is a champion,” says Interim Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Max Paul Friedman. “Her scholarship demolishes mythmaking and stereotype the way George Foreman hit the heavy bag. Her work restores sports to the center of inquiry about struggles for justice, reflecting the centrality of athletes to social change in America and beyond. We are lucky to have such a talented scholar in our corner.”

Runstedtler teaches several classes at AU, and her students are often lucky enough to hear her bring sports stories into her lectures and discussions. For undergrads, she teaches HIST-208 African American History: to 1877 and HIST-209 African American History: 1877 to Present. She teaches a graduate seminar, HIST-728 Colloquium in United States History II: since 1865, and this fall she will be teaching a new undergraduate class, Race, Resistance & Sports, cross-listed in History and American Studies.

Runstedtler also served as the inaugural chair of AU’s Critical Race, Gender and Culture Studies Collaborative (CRGC), from 2015-2018. Under her leadership, the collaborative brought together five interdisciplinary programs from across campus and served at the forefront of the university’s work towards inclusive excellence.

In 2020, the collaborative became an official department — the Department of Critical Race, Gender, and Culture Studies, which is continuing the work of the collaborative, producing scholarship and programming in both scholarly and creative venues. Professor of History Eileen Findlay, who serves as the department’s current chair, says that Runstedtler was critical to the department’s success and growth. “If not for Dr. Runstedtler’s persistent, creative labor to establish and consolidate the CRGC, we would not have the exciting, thriving department we have today.”