Research

Liberty and Security Magazine: Biography of a Metaphor

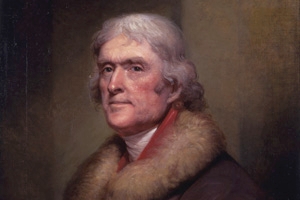

Thomas Jefferson, courtesy of Smithsonian Institute

This story comes from the Fall 2013 issue of Liberty and Security, the magazine for the Department of Justice, Law & Society. Read the entire issue here »

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ’make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

When Thomas Jefferson penned those words in response to a congratulatory letter from a small Baptist association in Danbury, Connecticut, on New Year's Day in 1802, the recently elected President likely had a few motives in mind. Paramount among them, according to Professor Daniel Dreisbach, were strengthening political allies and clearing up controversy over his refusal to declare federal religious holidays.

"Biography of a metaphor"

Jefferson did not, however, set out to invoke a metaphor that would influence scores of U.S. Supreme Court decisions and guide American thought on church-state relations for the centuries to come. But that he did – and Dreisbach has spent more than 20 years tracing its life through legal and political history. His 2002 book Thomas Jefferson and the Wall of Separation between Church and State is “a biography of that metaphor,” says Dreisbach, who earned a DPhil from Oxford University and a JD from the University of Virginia, one of Jefferson's pet projects.

Though Dreisbach is quick to point out that Jefferson didn't actually coin the “wall of separation” phrase, he explains how the statesman's words have become the organizing theme of the Supreme Court's church-state jurisprudence, using his words to “advance a particular interpretation of the First Amendment.” Jefferson's metaphoric wall has been used to settle Supreme Court cases throughout history, from an 1878 case on Mormon polygamy to a 2002 case on using publicly-funded vouchers to subsidize private school tuition. In the latter case, Justice John Paul Stevens took the wall metaphor to new heights in his dissenting opinion, writing that, “Whenever we remove a brick from the wall that was designed to separate religion and government, we increase the risk of religious strife and weaken the foundation of our democracy.”

Yet Dreisbach suggests that in writing the Danbury letter, Jefferson was simply trying to establish that religion was outside the President's scope of work as defined by the Constitution, and a matter more appropriate to state government and religious societies. “That wall was meant to separate state and federal government, with religion falling on the state's side of it,” he says.

Political institutions

Having painstakingly researched the context surrounding Jefferson's historic letter, Dreisbach claims that his intentions were more political than philosophical. “Sometimes we look back at these historic figures as if they were marble busts and forget that they were politicians,” says the professor. The 1800 presidential election was one of history's most hotly contested, according to Dreisbach, with Jefferson and his opponent, John Adams, running mud-slinging campaigns. Jefferson was accused of being a radical infidel, while Adams was portrayed as an enemy of religious freedom. The Danbury letter was a chance for Jefferson to set his record straight on his stance on the federal government's role in religious matters – a topic of intense debate in that era.

In the days before televised addresses, not to mention tweets, blogs and the 24-hour news cycle, letters were an important way for leaders to communicate with the greater public, according to Dreisbach. “It was not uncommon for civic and religious groups to write to the President in those days, and not uncommon for the President to respond to them personally,” explains Dreisbach. “Typically, the recipient would run it down to their local newspaper, who would print the letter, which other papers around the country would in turn republish.”

Uncovering the truth

Those Jefferson-era newspapers became key sources in Dreisbach's research, though his most primary source was the actual rough draft of the letter itself, housed within the Library of Congress. Dreisbach spent hours poring over the parchment-paper letter in a temperature-controlled room at the library, wearing gloves to protect the document and armed with only a pencil and a notepad, per library rules. The professor discovered that the transcriptions of the letter published since the mid-19th century contained several major errors, and that Jefferson had made several major edits, scribbling out words and phrases so thoroughly that Dreisbach had to call in the FBI's “questioned documents” unit to decipher them.

Today, nearly every surviving historic document has been archived digitally, a welcome convenience for Dreisbach, though he worries that the advent of key word searching makes it too easy for researchers to ignore the surrounding context of a given newspaper article or turn of phrase.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. More than two centuries after Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated as the third president of the United States and penned his famous words on the role of religion in national politics, President Barack Obama was sworn in on a weather-worn Bible belonging to preacher and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Issues of faith – including the very notion of separation of church and state – were among the issues debated on the 2012 campaign trail. While the world has changed in ways Jefferson could have never imagined, the political maneuvering around this debate would probably seem all too familiar.

--Professor Daniel Dreisbach previously served as a judicial clerk for a judge on the U. S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and as a public interest lawyer specializing in civil and religious liberties. He has been published in, among others, American Journal of Legal History, Constitutional Commentary, and Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Dreisbach's latest research looks at the influence of religion on colonial laws.