In 2017, Becca Peixotto wedged deep into Chaos—a reflection not of her state of being, but rather her location.

The colloquial name belonged to a maze of tiny underground passages, more than 30 meters beneath the surface and 200 from the nearest entrance to the Rising Star cave system in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind. It was there, tucked into a cramped opening just 15 centimeters wide and 80 centimeters long, bent around a corner, and positioned nearly upside down in the dark while fighting claustrophobia that Peixotto, CAS/MA ’13, CAS/PhD ’17, uncovered new details about a long since departed species.

The archaeologist, part of an international team of 21 researchers led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and supported by National Geographic, had been digging up bones—and digging into the information contained within them—since the launch of the expedition four years earlier, in November 2013. During their initial 21-day excavation that year, the “underground astronauts”—an all-female team of six scientists, including Peixotto, now a senior terrestrial archaeologist for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation in support of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency—unearthed fossils belonging to the previously unknown species Homo naledi, a 250,000-year-old primitive human relative. The team found the initial deposits that led to the discovery—dubbed one of Smithsonian magazine’s top 10 of the decade—in a section of cave now known as the Dinaledi Chamber. During Peixotto’s subsequent visits to South Africa, the cave offered up more remains of our distant cousin—but additional hominin fossils lay hidden in Rising Star’s two kilometers of passageways.

In November 2021, after four years of analysis and research, the team detailed in a pair of papers in PaleoAnthropology the fruits of Peixotto’s 2017 descent to Chaos: the first partial skull of a Homo naledi child, pieced together from 28 cranial fragments and six teeth. The discovery provides new insight into the species’ development and new questions to ponder, including how the four-to-six-year-old child came to a final resting place in a remote part of the cave system and to what extent other members of the species played a role.

The findings served as another reminder that Peixotto’s profession can derive big meaning from tiny fragments. Whether the history in her hands is 200 years old or 250,000, “The past doesn’t go anywhere,” says Peixotto, who contributed to a paper describing the context, circumstances, and location of the skull’s discovery. “It impacts us in the present, and it informs our future. There’s a visceral connection with people from the past. This thing may have happened to someone else, but it happened right where I’m standing. They stood here too. We’re part of a continuum. And it doesn’t end with us.”

The star discovery has a name: Leti, short for letimela, a Setswana word meaning “the lost one.”

Fortunately, Peixotto has a keen sense of direction, thanks to 13 years of outdoors education and a strict adherence to safety protocols. Had it been us, we might’ve been the lost ones.

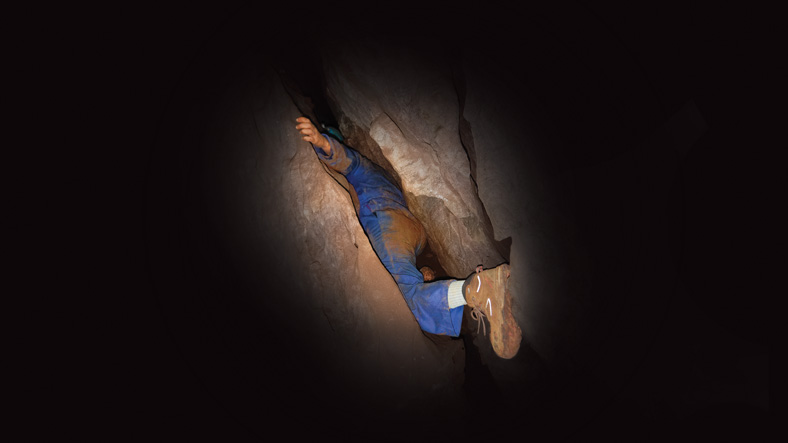

Peixotto excavates Homo naledi fossils in the Rising Star cave system in 2017 (Elen Feuerriegel)

Peixotto and biological anthropologist Marina Elliott were part of a small team that followed up on a tip from cave explorers of possible fossils. Years in Rising Star taught the researchers that despite the 14 inches between them—Peixotto stands around 4-foot-10 and fellow underground astronaut Hannah Morris is nearly 6 feet tall—clearing tight spaces like Superman’s Crawl, a 10-inch-high opening en route to the Dinaledi Chamber, “is not so much about size as the way you move your body,” says Elliott, a researcher at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. “The height [difference] just meant that each one of us had to negotiate the cave in our own unique way.”

In 2017, the group navigated 12 meters past the Dinaledi Chamber, squeezing into Chaos and over fallen boulders. But at the edge of the narrow passage, Elliott realized there was no negotiating. “I don’t bend that way,” she said, before looking to Peixotto to carry on. “Sorry, man.” Peixotto wedged her helmet in the gap so the light shone down on her (tight) workspace. She then oriented her face and hands to photograph and document what appeared to be bone fragments. Colleagues kept their hands on her foot so that she didn’t topple over.

Wider passages in Rising Star gave Peixotto the flexibility to set up a square, enabling her to methodically excavate in levels with toothpicks and brushes and examine each bone’s contextual relationships. But Chaos was not one of them. A contorted Peixotto removed items from the sediment and handed them to Elliott one by one through a gap in the rock, careful that neither she nor her gear fell and crushed the delicate shards below. Each one was numbered and labeled, swathed in bubble wrap, and placed in Tupperware for safe transport to the surface. The team knew it had teeth and bits of thin, curved cranium. Lab science later confirmed that these remains were hominin and Homo naledi. The 34 fragments became part of the expedition’s 2,200 extracted to date.

Peixotto, who last traveled to South Africa in 2019 while curating an exhibit on Rising Star for the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, thought in 2013 that the expedition would last only weeks and yield few bones: “a neat little blip on my CV,” she says in late 2021. “I had no idea that I’d still be talking about that site beyond just a fun story at the bar. I had no idea I’d still be involved in research.”

Like the tortuous passageways that were once her commute, “it certainly changed my trajectory.”

Rebecca Stone Gordon, CAS/BA ’96, CAS/MA ’00, had the flu one day in 2013, and a restlessness that only refreshing a Facebook feed could cure. As she feverishly scrolled, Stone Gordon stumbled upon BioAnthropology News’s job posting for the expedition. The ad sought archaeologists and paleoanthropologists with caving and climbing experience who could work in tight spaces and travel to South Africa on short notice.

Stone Gordon had a flash that cut through her brain fog: Peixotto, her knitting buddy and graduate anthropology colleague who was well-versed in ropes and harnesses from her tenure with Outward Bound, a nonprofit that provides wilderness education programming to 150,000 people each year.

Despite Peixotto’s reservations—a historical archaeologist deals in artifacts that are centuries old, while a paleoanthropologist handles remnants that date back hundreds of thousands of years—Stone Gordon continued to push. “It might have been the fever that made me fixate on it, but this set of skills screamed [Peixotto’s] name in boldface,” she says.

Peixotto caved—then began working in one three weeks later. “Our knowledge is cumulative,” she says now of making changes and taking chances in her career. Hers has been accumulating since childhood.

She grew up with archaeology in her bones but not on her radar. Peixotto loved digging near her grandparents’ old farmhouse in Vermont. She also dug history, museums, and old treasures but, “it never occurred to me that archaeology was a career,” Peixotto says. “I’m sure I watched Indiana Jones, but that’s just a fictional character doing silly things. How do you actually get to be one of those?”

She found the answer at AU. Peixotto enrolled in the anthropology graduate program in 2011 for two reasons: to infuse more anthropology education into the Outward Bound programs she had spent five years managing and to contemplate a career move that would be easier on her body. When she took an archaeology seminar with Professor Lance Greene, she was hooked—it was the ideal mix of science, history, and the great outdoors. Peixotto was captivated by the way Greene and classmates “talked about using science and artifacts to recover the stories of people who weren’t in the history books,” she says. “Not famous people, but everyday people on the margins. I was intrigued by the social justice aspect of that.”

She spent chunks of the next five years nursing that intrigue, gathering and analyzing artifacts left behind by Maroons—Africans and African Americans who formed their own hidden communities after escaping slavery—for Professor Dan Sayers’s Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study (see sidebar). In summer 2012, Peixotto took a weeklong break from leading wilderness expeditions in the Sierra Nevada to attend her first AU field school at the swamp, located near the Virginia-North Carolina border. She learned how to set up coordinate grids in the earth; how to record information vertically, horizontally, and contextually; how to use “gizmos,” as Sayers calls them, to ascertain distance and other measurements; and how to map and take accurate field notes.

Peixotto became an assistant laboratory supervisor and TA before establishing her own research project on the swamp. Sayers soon noted that she was the “the most naturally gifted teacher” he’s seen; she worked creatively without cutting corners and brought a good attitude to a demanding—not to mention humid—workplace.

“Not every archaeologist is that way. You get a lot of people who aren’t necessarily self-centered, but in their own brains, and you’re distracting them when you talk to them,” he says. “[Peixotto] understands she’s part of a team, that there has to be a flow of information,” and that teachable moments can be excavated from almost anywhere.

It was why as grad students, she and Stone-Gordon worked an anthropology day—organized by Professor Rachel Watkins—for AU’s Child Development Center that featured small dig sites so that preschoolers could use their hands to uncover “artifacts” in the sand. Why, analyzing glass for her master’s thesis, she secured a monthlong loan of a portable X-ray fluorescence machine to provide training opportunities for her fellow AU students and members of the archaeology community. Why she’s been an American Association for the Advancement of Science IF/THEN ambassador since 2019, inspiring women and girls to pursue careers in STEM. And why the Perot Museum exhibit she curated, Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind, not only displayed fossils and highlighted researchers’ racial and gender diversity, but also provided a physical representation of rock walls so that museumgoers could feel Rising Star’s tightest squeezes.

Part of archaeology’s wonder is sharing it with others.

The pandemic relegated Peixotto’s three-dimensional career to two-dimensional screens, but the depth of her archaeological work remains.

Since 2020, the Hawaii-based Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency contractor has worked with universities and other partners to develop archaeology plans and organize staffing to locate the more than 70,000 US servicemembers still listed as missing in action. Peixotto’s main focus is World War II.

She believes in the DPAA’s mission to try to find answers for families who’ve sought them for as many as eight decades. It’s also personal. Peixotto was a military kid; her father, Air Force lieutenant colonel Roland E. Peixotto Jr., was killed in the line of duty in a 1992 helicopter crash during a training exercise in Utah.

Even though Peixotto does not interact directly with families, “they’re always in the back of my mind. I think about that on a personal level, what it means to know what happened to your loved one,” she says. “[These soldiers] went off to serve with the best of intentions, and they didn’t come back. Their sister or child or grandchild has no idea what happened to them, and so some closure can be meaningful for families and add to the layers of stories that they’re able to pass down.”

A decade in archaeology has kept Peixotto challenged—to solve problems in the dirt, lab, or office, and to find, verify, and amplify stories that might otherwise go untold.

She occasionally wonders, too, how our story will read in 200 years, from the masks and medical waste that will leave an archaeological signature to the layers that will follow.

“It’s interesting to me what the future will make of all that,” she says.

If we’re lucky, another Peixotto will reach in deep, upside down and around a corner, to begin to piece together the meaning of our chaos.

Dismal Swamp, Remarkable Story

Two hundred square miles of forested wetlands between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina, are home to ticks, snakes, 200 species of mammals (not all friendly), vines, sinkholes, and as Sayers, Peixotto, and other AU researchers have discovered, a tradition of defiance and community.

Sayers launched the Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study as a doctoral student at William and Mary in 2003. As he began putting his 22-inch machete and trowel to work in the swamp’s interior, he unearthed islands and evidence of habitation beneath the surface: stone tools and weapons, ceramic pipes and vessels, and markings suggesting raised log cabins and firepits. The harsh landscape was once a refuge for Indigenous people fleeing colonization in the early 1600s and Africans and African Americans escaping slavery from the late 1600s to the Civil War.

The Great Dismal Swamp hosted five AU summer field schools, spawning expansive research. Sayers’s 2008 dissertation became the 2014 book A Desolate Place for a Defiant People. In 2013, Peixotto analyzed glass in the artifact collection to understand its age. For her 2017 dissertation, she discovered new islands to the northwest of the original dig site. Years of analyzing the swamp connected Peixotto to a powerful narrative of “people living under the absolute worst circumstances, being enslaved, finding a way to wrench themselves from that and creating their own communities,” she says. “It’s a story filled with resilience that more people need to know about.”

After 10 years, Sayers reached a “plateau,” and hasn’t returned to dig since 2014. He can likely be lured back with the right research question or another “damn good reason,” but he won’t commit one of the great sins of archaeology: “excavating for the sake of excavating.” Sayers, colleagues, and students collected thousands of artifacts, and with them, clues about people he reveres. “Now the question is, is one lifetime enough to analyze what we’ve found in ways that do it justice?”