Michael Watson returned from the kitchen of his North Carolina loft and informed his guests that dinner would be delayed. The chicken, he reported, was too "rounded"—it needed more "points." Points? Watson's guests, well into their cocktails and conversation, reacted with bewilderment.

The stage-lighting designer then described how, for him, tactile sensations always accompanied the taste of food. "The feeling sweeps down my arm into my hand," he said, "and I feel shape, weight, texture, and temperature, as if I'm actually grasping something."

Nearly everyone laughed at Watson's disclosure that night in 1979. Everyone except a young medical resident, Richard Cytowic, CAS/MFA creative writing '11, who barely knew Watson at the time. Cytowic had just read The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book about a Vast Memory by Russian neuropsychologist A. R. Luria.

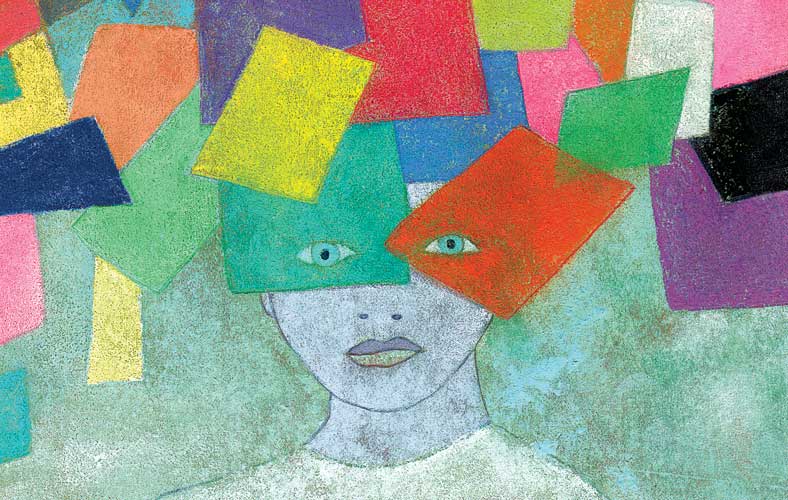

The book presented the case of a man who had, along with eidetic (photographic) memory, a harmless but unusual neural condition known as synesthesia, whereby one sense perception triggers a second, usually in a different sense. Luria's subject, Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia across multiple senses. When a bell was rung, for instance, Shereshevsky not only heard it but also tasted saltwater, saw "a small, round object" rolling in his field of vision, and felt "something rough like a rope" with his fingers.

Watson, though a synesthete, had never heard of synesthesia. ("You mean there's a name for it?" he said, with mixed astonishment and relief. "People have always said I'm just crazy.")

Nor, it turned out, had Cytowic's fellow medical residents heard of the condition. When told about Watson, they suspected a brain injury or malformation. And when Cytowic expressed a research interest in synesthesia, they advised him to avoid the topic. It was too impressionistic, too dicey, they warned. It would ruin his career.

At the time, B. F. Skinner's behaviorism dominated psychology and associated fields, and for a behaviorist, synesthetes' perceptions would have held no interest, being unverifiable in the lab and maybe even faked in a grab for attention. As a result, synesthesia had largely been forgotten; any literature on the subject, aside from Luria's book and a few obscure papers, dated back a century or more.

Yet despite his colleagues' admonishments and the overall lack of professional interest in synesthesia, Cytowic found it utterly compelling and ultimately made it his life's work. The intellectual contrariness behind this decision has roots in his personal story, he says. He grew up in the straitlaced 1950s, the son of a Trenton, New Jersey, doctor who had sidelines in magic tricks and hypnotism.

By age 10, Cytowic had realized that he was gay and learned from religious authorities that such people as he were headed for eternal fires. Like mesmerism, magic, and homosexuality, synesthesia was a forbidden topic, he says, and he'd always gravitated to the forbidden. "Anything," says the neurologist and author, "where people tell me, 'This is not supposed to be,' that's something I am drawn to."

Ten years after that dinner in Michael Watson's loft, Cytowic published Synesthesia: A Union of the Senses (1989). Now considered a classic text, the book featured research conducted on 42 synesthetes, Watson among them. It mapped which kinds of sense perceptions could trigger which synesthetic responses, established criteria for diagnosis, and undertook early brain-imaging studies with the primitive equipment then available.

After the publication of Synesthesia, Cytowic heard from more synesthetes. By now, he has communicated with a thousand of them and tested several hundred, some of whose stories appear in a more recent book, Wednesday Is Indigo Blue (2009). Coauthored by Cytowic and neuropsychologist David Eagleman, this updated account of synesthesia benefits from 20 additional years of research by the authors and some two dozen colleagues who have entered the field since Cytowic's first book.

Wednesday catalogues and illustrates some of the numerous varieties of synesthesia: a woman for whom music evokes tactile sensations (a "dull throbbing at the back of her neck for trombones," violins breathing in her face, and so on); a man for whom food tastes trigger color sensations (he's "especially fond of foods that taste blue, such as milk, cheese, all citrus fruits, vanilla"); and many synesthetes for whom units of time (the days of the week, the months of the year) evoke responses that include location in space ("November hangs above me to the left") and color, as in the perception that gave the book its title.

The book also summarizes research that proves the authenticity of synesthesia—that synesthetes are emphatically not "faking it." Over the years, Cytowic and others developed a regime of tests and retests of synesthetes' responses to certain triggers—the colors evoked in them by a given set of numbers or letters, for instance. The results show consistency—in some cases over many years—that would have been impossible to fake. Other tests, using a technique called Stroop interference, show synesthetic responses to be automatic rather than voluntary. For any remaining skeptics, evidence from MRI brain scans establishes conclusively that synesthesia really happens.

Okay, but why and how? Cytowic and Eagleman theorize that synesthesia results from elevated levels of communication, or so-called cross talk, between brain areas that specialize in different modes of perception—the area for musical pitch and the area for color vision, for instance. Cross talk plays a crucial role in everyday mental functioning, allowing us to integrate the diverse and disconnected sense perceptions (colors, shapes, movements, spatial locations, pressures, sounds, temperatures, textures, and smells) involved in one event into a unified picture of what's happening right now in our immediate vicinity.

In synesthetes, the cross talk is simply louder, possibly because their neural networks, the biological circuitry used by cross talk, have somehow been "disinhibited." Some people who take LSD experience this kind of disinhibition, along with temporary synesthesia. Which chemical substance performs the same function as LSD in the brains of natural synesthetes, says Cytowic, is a topic for future research.

In keeping with the idea that neural cross talk happens in everybody's brain, Cytowic has hypothesized that we all may be synesthetes to a degree, an idea reinforced by the near universal tendency to move in time with music. That response may not be genuine synesthesia, he acknowledges, because the movements don't take a consistent form from one episode to the next, but it does show that different brain areas are hardwired together in everyone.

It's another subject for further research, but Cytowic guesses that nonsynesthetes are really synesthetes whose synesthetic perceptions remain below the level of consciousness. This view gains support from studies of experienced meditators showing that they are more disposed to synesthetic perceptions during meditation than their less experienced counterparts, not to mention the average nonmeditator. "If you ratchet down all the external noise," explains Cytowic, "then what's obscure, what's hidden, can be unmasked."

The authors of Wednesday Is Indigo Blue report that synesthesia runs in families. As an inherited trait, does it perform what evolutionary biologists call an adaptive function? Cytowic thinks it does, but it also can come with notable disadvantages. A small minority of synesthetes, for instance, have to live cloistered lives to avoid the sensory overload they would face in a noisy, brightly lit urban space. Synesthetes, more than the average person, also tend to suffer from a poor sense of direction. They also may have trouble reading maps and telling left from right, and many do poorly at arithmetic.

On the other hand, Cytowic says, many synesthetes benefit from remarkable memory, using their perceptions as mnemonics—synesthetic colors to help them remember names and telephone numbers, for example. Not surprisingly, Shereshevsky, the subject of A. R. Luria's study of eidetic memory, also belonged to this subgroup of memory champions. Another member of the group, a synesthetic librarian of Cytowic's acquaintance, says she has a hard time understanding why people need to use the card catalog. She has her library's collection memorized; why can't others do the same? (Many synesthetes grow up thinking that everyone perceives the way they do and possesses the same unusual abilities.)

Synesthetes also display a talent for finding connections among dissimilar things, a trait that comes in handy for artists. The list of synesthetes among famous artists runs from Vladimir Nabokov, author of Lolita and Pale Fire, to rockers Stevie Wonder and Eddie Van Halen and classical composers Liszt and Rimsky-Korsakov, who, according to Wednesday Is Indigo Blue, "are said to have disagreed with each other over the color of musical keys." French composer Olivier Messiaen put his sound-to-color synesthesia at the center of his work, inventing a method of composition intended to "paint the visible world in sound," while jazz pianist Marian McPartland (whom Cyotowic has spoken with but never tested) described for him the pinkness of A-natural.

Visual artist David Hockney, whom Cytowic did test, paints stage sets for ballets and operas while listening to recordings of the works to be performed. For Hockney, music triggers visual perceptions, such as colors and shapes. "I know visually when the color or the lines [of a set] fit the music," Hockney told Cytowic. "We went through 27 versions of The Rite of Spring sets before they fit the music. . . . Most of the problem there, however, was getting the color right, rather than the lines."

Forty percent of the online Synesthesia List's members (a nonrandom sample, Cytowic admits) make their living in an artistic field. Of course, the universe of synesthete artists includes Michael Watson, the theatrical lighting specialist who helped launch Cytowic's research. Like most synesthetes, Watson, who died in 1992, valued his condition. Though he didn't talk about it much, in hopes of avoiding ridicule, he saw it as something that deepened his experience of the world.

"The first bite I take of a new course [in a meal] is an urge for me to look in a new direction," he once told Cytowic. "These new experiences are frequently very sensual, although sometimes they are erogenous as well."

A gifted amateur cook, Watson used his synesthesia instead of recipes. "He guides himself," write Cytowic and Eagleman, "by a rough idea of what he wants the final dish to feel like, adjusting the ingredients and seasonings by trial and error—for example, altering the flavor's shape to make it 'rounder,' giving it more 'inclination,' 'sharpening up the corners' to give the vertical lines more heft, or adding 'a couple of points' to the overall shape. . . . When a dish's shape eventually matches his starting idea, a 'eureka' feeling comes over him." The process sounds remarkably similar to David Hockney's procedure for painting stage sets.

As for the chicken that Watson found insufficiently pointy that evening back in 1979, Cytowic explains that, for Watson, the perception of points—"like running my hand over a bed of nails," as he described it—was triggered by "lemony, sour-y" flavors.

So how did the chicken taste after Michael Watson added points?

"It was great," Cytowic says enthusiastically.