A productive conversation about policing in a world of license plate readers and facial recognition software might begin by thinking back to parchment and powdered wigs.

The framers of the Constitution devised a construct of checks and balances, diffuse power, and individual rights like trial by jury and protection from unlawful search while still reeling from the centralized, privacy-invading rule of King George III. Power—and strategically checking those who would abuse it—serves as the lens through which Washington College of Law professor Andrew Guthrie Ferguson imagines a better way forward in “Surveillance and the Tyrant Test,” published in the Georgetown Law Journal in December 2021.

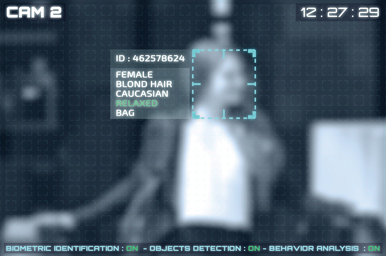

Surveillance technology provides governments and the 18,000 police agencies that enforce their laws new means to track and control citizens. What to do about it—keep, abolish, or regulate—is a debate that’s fiery but not always fruitful. Ferguson doesn’t offer a definitive solution. Instead, his “tyrant test” distills a decade’s worth of privacy law and technology research to identify shared cynicism as common ground from which to start the conversation. The tyrant test holds that restrictions on big data policing should work backward from the assumption that governments in power—the metaphorical tyrants—will abuse power, and that “overlapping community institutions with real authority and enforceable individual rights” must be implemented as a legitimate check.

“Both civil libertarians and people who are supportive of police power can recognize that, at our core in the founding of America, we were distrustful of power,” Ferguson says. “[The tyrant test] allows people who might not see the world the same way a place to begin the debate that’s more constructive.”

It was while serving as a DC public defender and hearing in court how police had stopped his clients in “high-crime areas” that Ferguson began exploring the objectivity of that data and how new technology distorts old law. Today, he is one of the nation’s leading experts on predictive policing and the intersection between the internet of things and the Fourth Amendment. He testified before Congress on facial recognition software in 2019, and his 2018 book, The Rise of Big Data Policing, gave rise to the term.

Ferguson draws on that expertise to present the tyrant test as a best course of action after first examining where these competing lenses fall short. He details how our default—a lack of regulation for the vast majority of police technology—leaves citizens largely unable to hold police accountable and how abolitionists face long odds of achieving revolutionary change in the near term despite successful community mobilization. Even the technocratic lens, a pragmatic approach to regulating police technologies that emphasizes transparency and public accountability, can lack teeth, Ferguson writes.

He knows there is both strong disagreement on how to approach policing technologies and limited mechanisms for productively parsing through those wedges. The tyrant test, Ferguson hopes, will spark discussion among those who wish to continue doing the hard work on a hard issue.

“The conversation has sort of stopped, but there are governmental actors, activists, and academics who are looking for a new first principles way forward,” he says. “Here’s another suggestion.”