Whaddya think you're doing, boy?

Isn't he an ugly one!

It's not real, you tell yourself. But the fear, the hatred—it's visceral. A sharp kick to your chair takes your breath away. Glass shatters. More screaming. Then a man leans in, his chillingly calm voice cutting through the chaos unfolding around you. Your eyes are closed, but you can imagine a sick smile spreading across his face as he snarls in your ear.

I'm going to stick this fork in your neck.

Enough. You've had enough. You lasted 92 seconds. You're overwhelmed by emotion: terror, sadness, anger, shame. Ninety-two seconds—that's it?

The simulation of a sit-in at Atlanta's Center for Civil and Human Rights left students from the School of Public Affairs (SPA) shaken. It was the first day of an immersive field trip through the South for Gregg Ivers's Civil Rights Movement class, during which they would confront the reality of a dark chapter in this country's history.

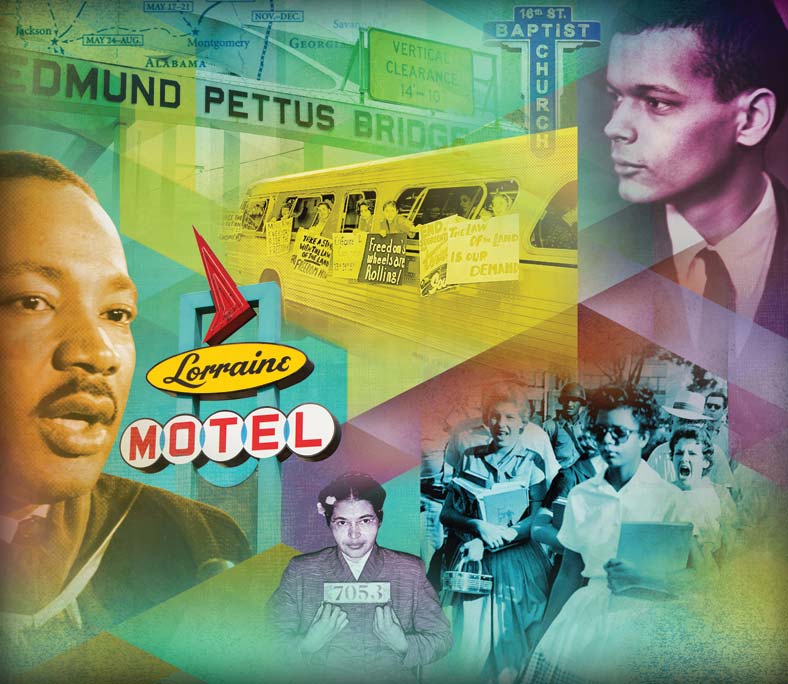

Ugly and raw as the experience was, the simulator provided the perfect entrée to the students' whirlwind spring break trip, funded entirely by American University. Over the next seven days, they traversed five states and a decade of Civil Rights history, retracing the footsteps of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and scores of other people whose names were never etched on memorials or recorded in books, but whose extraordinary bravery and selflessness changed the course of American history.

As the students reflected on their first day in Atlanta, they thought about the four black freshmen from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, who, on February 1, 1960, sat down at the now famous Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro.

Would I have the courage to do that?

It's a question they would ponder often throughout the trip—as they walked the corridors of Central High School in Little Rock, crested the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, and boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Birmingham.

Well, would I?

It's one thing to read about James Meredith, the first African American student admitted to the segregated University of Mississippi in 1962, or to watch grainy, black and white footage of the deadly riots that erupted two days before he arrived on campus. It's something else to step inside the grand Lyceum—the oldest building at Ole Miss, erected by slaves in 1848—and roam the same hallways where the political science major walked when he registered for classes, surrounded by armed US marshalls.

"There's nothing more powerful than sacred space," says Lonnie Bunch, CAS/BA '74, CAS/MA '76, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. "If you go to Medgar Evers's home and stand under the carport where he was killed, you look around and see where people hid behind the hedges. Or you'll go down the road and see shotgun houses from 70 years ago and you can almost feel and breathe the air of what those people experienced. It is something as important as any memorial on the Mall. It will stay with you forever."

When Julian Bond, a founding leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), former NAACP chairman, and longtime AU distinguished adjunct professor, died in August 2015, Gregg Ivers took over SPA's Civil Rights curriculum. Ivers wasn't just standing on the shoulders of a giant; he was filling the shoes of a close family friend.

Ivers's father Mike owned a men's clothing store, Campus and Career, on Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard) in Atlanta, from 1962 to 1968. The store was located around the corner from Morehouse and Spellman colleges and across the street from Paschal's, a prominent African American-owned eatery and popular gathering place for preachers, politicians, and activists. (The Paschal brothers often posted bond for protestors and gave them a warm meal after they were released from jail.)

Martin Luther King Jr. and his father, "Daddy" King, and John Lewis— they would all start out at Paschal's for a strategy session over fried chicken and, on occasion, end up at Campus and Career for a suit. "I grew up with these guys," Ivers says. "But Julian, he was always a family favorite.

"When he died, I knew I needed to do something to honor a great man and a friend. More importantly, the work needed to go on. So many students have sanitized notions of the Civil Rights Movement. It became a personal mission for me."

That mission would take him to the apex of the Edmund Pettus Bridge on a sunny December afternoon in 2015. It was one stop on a tour of Civil Rights landmarks across the Deep South to gather material for his course syllabus. Here, on the bridge for the first time, he imagined "[Sheriff] Jim Clark and his posse waiting at the bottom" for the protestors marching for voting rights on what would become known as Bloody Sunday. Ivers had an epiphany.

"I had to figure out a way to get students to that bridge." It would be, he knew, something that would stay with them forever.

Fifteen months later, eight students gathered near a modest memorial at the foot of the steel structure that carries four lanes of US Route 80 across the Alabama River. It was another sunny day, albeit unseasonably chilly for March in the Deep South. The students had just walked in twos across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, just as protestors, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, had done on March 7, 1965.

"You're not on sidewalks, you're not in parks, you're on battlefields," Ivers said as the students grappled with the gravity of what had happened on that spot 52 years ago. It was a refrain he'd repeat often throughout the trip.

While the power of this particular stretch of dilapidated highway was palpable, students found the lack of acknowledgement disconcerting.

Selma had been a Civil Rights flashpoint, and yet the bridge, named for a Confederate general and Grand Dragon in the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, was only declared a National Historic Landmark four years ago. The median where Lewis—now a congressman, but then a young man just a few years older than the AU students—was brutally beaten by Alabama state troopers is now a generic weedy strip flanking a check-cashing store and a used car lot. "I wondered if [people] driving across the bridge even knew why we were there," says Aubrey Stuber, SPA/BA '17. "Did they notice we walked in twos?"

Everyone processed the experience in their own way. Some journaled, others prayed, and one student, Laura Hoyos, SPA/BA '17, wrote a poem. "They say the grass is greener on the other side / I wonder if this grass under my feet was once stained with the blood / of those who fought for freedom and if so / where is the other side?"

Madison Guare, CAS/BA '19, had walked across the bridge arm-in-arm with Julian Bond during a high school spring break trip in 2015, just five months before his death. On this day, she walked for her late mentor, the man who convinced her to reject the University of Vermont and come to AU and study under him.

"Selma was tough. I missed him there, and I mourned for my new friends who wouldn't get to know him," says the sociology major from Richmond, Virginia. "In the pain I felt that my friends couldn't know Julian, I realized that Julian was the reason I know my friends. I would never have found myself at American if I hadn't first found myself walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge two year earlier."

Ivers's Civil Rights course was conceived under the prestigious AU Scholars program, an intensive, two-year, living-learning community for select incoming freshmen. Each year about 150 students are invited to participate in the program, which "underscores AU's commitment to provide substantive research opportunities to undergraduate students," says Jamie Wyatt, learning communities director. The goal, she says, is to help "curious, engaged, high-achieving students push their own boundaries in college."

AU Scholars stresses research and writing skills. Students take a special seminar each semester and engage in cocurricular programming that takes them to sites across DC. The program culminates with an experiential learning opportunity during the second semester of sophomore year. AU Scholars have studied school segregation in Northern Ireland, dug into sustainable farming in Cuba, and traced migration in Brussels.

"Students get experience that they otherwise might not have until their junior or senior years—or even grad school," Wyatt says. "It certainly makes them more competitive when it comes to merit awards, internships, and jobs after college."

It took a lot of heavy lifting to get funding—about $1,500 per student—but SPA and AU Scholars, along with the vice provost for undergraduate studies, Jessica Waters, and the interim vice president of Campus Life, Fanta Aw, worked together to make it happen.

"That's how transformative we believe these experiences can be," Wyatt says.

At the Freedom Rides Museum in Montgomery, the AU group learned about the 21 college students—none of them older than 22—who penned farewell letters and wills before boarding a bus in Birmingham bound for Montgomery, where they were met by a violent mob. At a Memphis bookstore, they had a serendipitous meeting with Ole Miss alumnus Lyman Aldrich, who admitted that he "always regretted not extending a hand to James Meredith." At Central High School they sat in the worn, wooden chairs perhaps once occupied by the Little Rock Nine. While they listened to National Park Service ranger Randy Dotson recount details about the relentless hazing the African American students endured just to get an education, they watched a rainbow of current high schoolers whisper, joke, and walk hand-in-hand down the hallway.

And at every turn, AU students confronted their privilege. They thought deeply about the social justice issues most important to them, and questioned whether they were authentically living their values. They contemplated how much things have changed since Birmingham public safety commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor turned firehoses and police dogs on children in Kelly Ingram Park—and, in light of recent racial incidents on AU's campus, how much more change still needs to happen. They realized the importance of empathy and of a moral compass. They witnessed extreme poverty through the windows of a Greyhound bus and were humbled by Southerners' graciousness and famed hospitality. Over the course of a week, they saw a world that is at once ugly and beautiful, and they questioned their place in it.

"It's easy to say you'd have the courage, but people like John Lewis knew they could die and were undeterred. They did what they thought was necessary without any regard for their own safety," says AU Scholar Scott Brenner, SPA/BA '19. "I don't know if I could put myself in a situation where I could die."

He's not even sure, he says, if he knows yet what is worth dying for.

When Rosa Parks was ordered to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery city bus in 1955, she said, "I thought of Emmett Till, and I just couldn't go back." As the students stood at the bus stop on Montgomery Street, where she was arrested for disorderly conduct, they wondered what Parks might inspire them to do.

"I chased resilience through the American South," Madison Guare says. "I watched the movement stumble. I hurt for the economy of Alabama, and I wept for the girls lost in their church. I know what to do next because of what I learned from them. I am recommitted to talking when it is inconvenient and speaking up for people who power ignores. I am reminded that the march goes on."

AU civil rights tour, March 12-18, 2017

Center for Civil and Human Rights, Atlanta, Georgia: The highlight of the museum, which opened in 2014, is the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection. The exhibit is spare by design; books from King's personal library, many annotated with handwritten notes, and drafts of his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" are displayed under glass in a dimly lit room, allowing the civil rights leader's powerful words to do all the talking. While the center devotes much of its 90,000 square feet to the Atlanta-born King and the movement he led, it also features exhibits that explore contemporary human rights struggles around the globe.

Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site, Atlanta, Georgia: The three blocks where Martin Luther King Jr. was born, lived, worked, worshipped, and is buried were preserved by the National Park Service in 1980. Sites include King's modest frame house at 501 Auburn Avenue, where he was born on January 15, 1929; fire station No. 6, Atlanta's first racially integrated firehouse; and Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King's father and grandfather served as pastors for nearly 80 years altogether. Visitors can sit in the timeworn pews and listen to King's "Drum Major Instinct" sermon, delivered at Ebenezer two months before his death.

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama: Birmingham's first African American church was the site of the September 15, 1963, bombing that killed four young girls. The church, which still serves a congregation of about 500, is adjacent to Kelly Ingram Park, where on May 2, 1963, public safety commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor unleashed police dogs and fire hoses on child protestors. More than 2,000 kids, some as young as seven, were arrested and jailed for up to nine days.

Negro Southern LeagueMuseum, Birmingham, Alabama: Jackie Robinson was, quite literally, a game changer. Before No. 42 desegregated America's pastime, starting at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, African Americans were relegated to the Negro leagues, created in the 1880s. Given the museum's location in the shadow of Regions Field, home of the Birmingham Barons (formerly the Black Barons), it's no surprise that the exhibits focus on the Negro Southern League, which operated from 1920 to 1951.

Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama: Shortly after leaving Brown Chapel AME Church, singing "Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round," more than 600 marchers moved slowly up the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965. Waiting for them on the other side: a posse of Alabama state troopers armed with billy clubs and tear gas. Eight days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson called Selma "a turning point in man's unending search for freedom" and introduced the Voting Rights Act, which was passed in August 1965

Freedom Rides Museum, Montgomery, Alabama: Before they boarded the Greyhound bus bound for Montgomery on May 20, 1961, 21 college students prepared wills and wrote farewell letters. They were prepared for the worst—and they were met with it when they arrived at the Greyhound terminal off Court Street. The building's exterior, including the "colored only" sign, looks exactly as it did when John Lewis and the other Freedom Riders rolled into town. Inside, the station has been transformed into a small but powerful museum.

Southern Poverty Law Center, Montgomery, Alabama: Since its first victory against the Ku Klux Klan in 1979, the Southern Poverty Law Center has stuck to its winning strategy: cripple hate groups by seizing their assets. Today the nonprofit tackles a range of cases around immigrant justice and criminal justice reform. It also tracks 917 hate groups across the country—including 27 in Alabama alone. The center's Civil Rights Memorial, created by Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, is around the corner from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. served as pastor during the Montgomery bus boycotts.

Rosa Parks Museum, Montgomery, Alabama: We all know the story of Rosa Parks, the demure seamstress who, on December 1, 1955, refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery city bus. Fewer of us know details of the 381-day bus boycott that followed. Highlights of this museum, operated by Troy University, include an exhibit on another civil rights heroine: Jo Ann Robinson, who stayed up all night on the evening of Parks's arrest, mimeographing 35,000 handbills that called on blacks to boycott the buses. "The next time it may be you, or your daughter, or mother."

University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi: A bullet hole above the door of the Lyceum—the stately Greek Revival-style building where James Meredith registered for classes on October 1, 1962—and a memorial dedicated to the first African American student admitted to Ole Miss are all that remain of what many historians refer to as the last battle of the Civil War.

Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas: The Little Rock Nine were the first to test the 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education ruling that separate is not equal. Nine months after hundreds of members of the US Army's 101st Airborne Division escorted the nine black students into the school on September 25, 1957, Ernest Green became the first African American to graduate from Central High. Among those in the audience was a then unknown Baptist minister: Martin Luther King Jr.

Stax Museum of American Soul Music, Memphis, Tennessee: Stax was founded in 1957 by white siblings Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton amid fierce racial tension in south Memphis. The label placed 243 hits on the R & B top 100 and launched the careers of Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, and such racially integrated bands as Booker T. and the M. G.'s.

National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis, Tennessee: An appropriate coda to the trip, this powerful museum is built around the 16-room Lorraine Motel, where an assassin's bullet felled Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. Passages from King's prophetic final speech—delivered the night before his death—are etched on the wall outside room 306, which looks just as it did 50 years ago. "I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything."