Research

The Civil War’s Long Shadow

Even if you've taken the Red Line through the Fort Totten D.C. Metro station, you might not know much about the area's history. Beyond the rail lines, escalators, and surrounding neighborhood, there's a hidden story about slavery and survival.

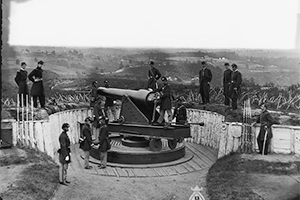

During the Civil War, there were forts all over Washington, D.C. Union forces provided refuge for runaway slaves in fortifications like Fort Totten (now a park and neighborhood of the same name), Fort Bunker Hill in modern-day Brookland, N.E., and Fort Stevens in the Brightwood, N.W. area.

Sue Taylor, public anthropologist in residence at American University, is studying the riveting, sometimes arcane, history of the nation's capital during the mid-19th century.

Descendants Project

Taylor partnered with the National Park Service on the African American Civil War Descendants Project. As principal investigator, she's expecting to complete a report by this fall, and NPS may use this information for educational programming in D.C. neighborhoods. Taylor is specifically looking at eight forts that are managed by NPS. She's covering the period from 1861-1877, from the outset of the Civil War through the end of Reconstruction.

Watch a video produced by the NPS about the project.

As part of this project, Taylor is hoping to talk with descendants of escaped slaves who came to D.C. It's a bit like finding a needle in a haystack, she says. She's also combing through archival records and relevant literature. "For example, if you have a name, you can go back and look at military records. And what you find is that Joe Smith was AWOL on that day. So it's very tedious stuff," she says. "But every now and then, you might find something exciting."

It's a regional history—mostly forgotten—about newfound freedom and resilience. "We're trying to tell a different story of Washington, D.C. during the Civil War. It's one that hasn't been told. We're interested in the fact that people in these communities sometimes don't even realize there was a fort there."

Burgeoning Communities

Slaves escaped from Maryland and Virginia and were taken in by Union soldiers. The ex-slaves were considered "contraband," essentially properties of war. They were given shelter and food, while continuing to work. Sometimes entire families came to stay in the forts. Women often performed domestic tasks, such as cooking and sewing, while many men ended up fighting for the Union Army. After the Civil War ended, many ex-slaves established roots in those neighborhoods, and their families remained there for generations.

At the time, Washington, D.C. was mostly rural, she says. Nowadays, even as it's become a hyper-wired metropolis, there are still shadows and remnants of those burgeoning communities. Schools were set up for newly freed African Americans, including the Military Road School—a building that now houses the Latin American Montessori Bilingual Public Charter School in the Brightwood neighborhood. At present-day Garrison Elementary School, in the Shaw/Logan Circle neighborhood, was a contraband camp where communities lived in tents. Taylor is also finding historical documentation about Fort Reno in Tenleytown, right near AU.

The Shiloh Baptist Church, now on 9th Street in Shaw, was established in D.C. by freed slaves from Fredericksburg, Va. "They missed their religion, so when they came here, they formed their own church," she says. In 2011, President Barack Obama and his family attended services at Shiloh Baptist Church on Easter Sunday.

One site that's been partially reconstructed is Fort Stevens, near Georgia Avenue and 13th Street. A plaque commemorates President Abraham Lincoln's visit there during the Battle of Fort Stevens. Although Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and his Confederate troops planned an all-out assault on the city, they were deterred by the arrival of Union reinforcements. "The fighting never really advanced beyond skirmishing and cannon fire," noted The Washington Post, in an article about the battle's 150th anniversary.

"I think people have no idea how close Washington, D.C. came to really being attacked. And trying to pull together that history, I think, is fascinating," Taylor says.

Storytelling

Taylor has been teaching at AU since 2006. She's currently director of the master's degree program in public anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences. With a background in issues like gerontology and medical anthropology, this is new terrain for her.

"You learn something about yourself when you really read history," she says. "We're focusing, as much as we can, on the people and the stories that we can find."