On Campus

Story of a Tennessee Chaplain

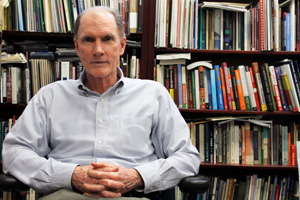

When asked where he’s from, Joe Eldridge thickens his Southern drawl.

“The great state of Tennessee,” he says. “I'm from the Smoky Mountains.”

Hailing from a small mountain town, AU’s university chaplain has crossed the globe to promote a message of social justice and human rights, from posts in Latin America to the office he’s kept at AU for the past 15 years.

Born to the family of a Methodist preacher, Eldridge describes his upbringing as being “nurtured in the womb of the Methodist church.” It was during his childhood that he gained his passion for human rights – a passion that would take him to Tennessee Wesleyan College and, eventually, seminary in Texas.

A committed activist in the civil rights and anti-war movements, Eldridge spent more of his seminary days out in the community than in the classroom. At the end of his studies, Eldridge found himself at a crossroads. He could either return to his hometown in Tennessee to work as a pastor, or he could take a giant leap.

“An inflection point of my life was after graduating seminary,” he says. “I was aware of my narrow horizons, my ignorance about the world. At least, I was aware of my ignorance. I said, ‘I want to leave the country.’ I didn’t even have a passport. I hadn’t left the country. I had barely left Tennessee.”

Because of his interest in issues of race, Eldridge applied to the Board of Global Ministries of the Methodist Church to work as a missionary in Africa. Soon thereafter, however, he was on his way to a post in Santiago, Chile, with no knowledge of Spanish language or Chilean culture.

The time in South America, however, proved defining for Eldridge. Toward the end of his more than three years in the Chilean capital, he witnessed the coup that put brutal military dictator Augusto Pinochet into power.

Eldridge guided foreign journalists to document the human rights violations taking place in the country.

“When journalists started coming in, they wanted to know what was happening,” he says. “Well, we knew what was happening. We tried to move around Santiago and not get arrested. We tried to help them figure out what was going on.”

When his friends and fellow social justice workers started disappearing, he returned home to the U.S.

Once stateside, Eldridge came to AU to pursue a master’s degree in the School of International Service. Over the next almost two decades, he would go on to build an impressive wealth of experience – all relating back to Latin America and his passion for the sanctity of human rights.

He directed the Washington Office on Latin America for twelve years, opened the Washington office of the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights (now Human Rights First), served with the United Methodist Church working on Latin American rights issues, and worked as a missionary in Honduras, before being thrown out by the country’s military for investigating abuses by the regime.

Finally, in 1997, Eldridge – now a father of three and grandfather of one – felt a call to the pastoral care he had studied in seminary decades earlier. The call landed him at American University.

“AU, this community, is my parish,” he says.

As university chaplain in the Kay Spiritual Life Center at AU, Eldridge has been a beacon of the university’s message of community engagement and service.

His office developed the Alternative Break program at American, sending students across the globe to witness social justice work in action. The Kay Center also hosts the Human Rights Defenders speaker series, and Eldridge helped establish the Social Enterprise master’s degree in the School of International Service. Under his watch, the Center – an interfaith house of worship – has expanded to include chaplains representing about two dozen faiths.

While he’s accomplished many things during his time at AU, Eldridge – always humble – believes his role is one that anyone can perform.

“When you are engaged in an act of kindness, of hospitality, of welcoming, of nurturing, really listening to someone, you are conducting yourself in a way that befits the title of chaplain,” he explains. “In other words, I don’t see this as a profession. Everyone on campus – staff and faculty – whether you are a person of a faith community or not, I think it transcends [that].”

Through his own acts of kindness, hospitality, and support for human rights issues, Eldridge has transcended his small-town mountain roots to impact people the world over. The Kay Center may house a number of vibrant faith communities, but it has only one Tennessee chaplain – a man whose story shows just how far commitment to a powerful ideal can reach.