Research

Voices Heard: SIS Professor Shows How Human Rights Activists Changed US Foreign Policy

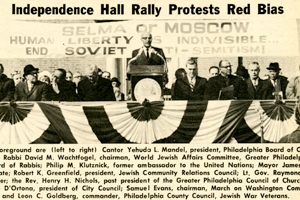

In her new book, SIS associate professor Sarah Snyder links domestic and international human rights activism. Credit: The Jewish Exponent.

In her new book, From Selma to Moscow: How Human Rights Activists Transformed U.S. Foreign Policy, Sarah B. Snyder avoids arbitrary dates and timeframes. She examines the “long 1960s,” from President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961 to Jimmy Carter’s in 1977. But in some ways, the long 1960s extend even longer. The lessons learned about US human rights policy during that period are still pertinent today, she says.

“It is not that I don’t think history is significant in its own right. But it seems to be a hook into how my students in SIS can think about history,” explains Snyder, an associate professor at American University’s School of International Service.

In her earlier book on human rights advocates in the Helsinki network, she studied the role of ordinary activists. With From Selma to Moscow, she’s mostly looking at how elite actors influenced human rights policy. “I think there are multiple ways that Americans who care about these issues can make their voices heard. But for the purposes of this book, I’m focusing much more on how they can be heard in Washington.”

Changes and Changemakers

Snyder details how members of Congress, agency officials, advocacy groups, and nongovernmental organizations helped put human rights at—or at least closer to—the front burner of American foreign policy concerns.

Among the changes during the long 1960s? Legislation that limited security and economic assistance to governments that violated human rights. New legislation also mandated annual reports on countries that were receiving assistance, which is why we now have the State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. Congress created the State Department’s Bureau of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs (now the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor), while elevating the head of that bureau to the assistant secretary level.

“I looked at efforts to lobby members of Congress and influence the executive branch, and also how people challenged foreign governments that were engaging in human rights violations. And what I found was that they were able to achieve a number of significant reforms,” she says.

For the book, she conducted extensive archival research in five different countries, five US presidential libraries, and personal papers of members of Congress. She also interviewed key figures: Rep. Donald Fraser (D-Minn.), whose hearings led to institutional reforms, and one of his aides, John Salzberg; James Becket, who co-wrote Amnesty International’s first report on torture in Greece; Mark Schneider, a top aide to Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass); and AU’s own Joseph Eldridge, the former university chaplain who also served as executive director of the Washington Office on Latin America.

Selma and Moscow

Snyder’s book had a different working title, but the version she used came late in the research process. She was reading a report about a rally on behalf of Soviet Jews in 1965—the same year as the heroic Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march in Alabama. A memorable banner over the stage read, “Selma or Moscow/Human Liberty is Indivisible/End Soviet Anti-Semitism!”

She had a researcher track down the photo, and a new, illuminative title was born. “I feel like what I’m doing is picking up on the connections that activists at the time were making, explicitly between the civil rights movement in the United States and the plight of Soviet Jews.”

Her book links domestic and international activism. She notes how civil rights figures served on human rights boards, and people like NAACP head Roy Wilkins and Martin Luther King Jr. called out hypocrisy in American foreign policy.

“They were pointing out the connections between the commitments that Lyndon Johnson was making domestically on civil rights and the commitments they thought he should be making on South Africa or Southern Rhodesia.”

The 1960s sparked immense social change, and she examines how the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements spurred greater interest in global human rights. It sounds counterintuitive, as racial strife at home and American soldiers dying overseas might provoke isolationism. But Snyder describes another outgrowth of the 1960s.

“It’s primarily about a breakdown in the Cold War consensus, and an increasing willingness of Americans, particularly members of Congress, to question the government’s foreign policy,” she says. “Between Vietnam and Watergate, there was an opening for more actors to be involved in foreign policymaking because the ‘imperial presidency’ model had been somewhat discredited.”

Transnational networks also expanded, she says, as more Americans studied abroad, did missionary work, and joined the Peace Corps.

Networks and Communities

Despite newfound activism during the 1960s and 1970s, Snyder observes a surprising level of continuity among presidential administrations.

“There’s no US administration where human rights are consistently prioritized over other priorities, and I’m not saying that they should be. But the Carter administration, despite being outwardly interested in human rights, still made a lot of decisions that suggested that Cold War priorities were more significant,” she says.

One of the book’s noteworthy findings is that the human rights community didn’t surface in the Jimmy Carter era. At times, progress was slow—she argues that Amnesty’s opening in the US wasn’t consequential initially—but there was a network in place.

Fast forward to today, and Snyder acknowledges that human rights groups face an uphill battle. With many Americans concerned about democracy and the rule of law domestically, it’s tough getting citizens worried about atrocities in Syria. Yet she hopes her book can show readers a well-documented, historical precedent.

“I think it offers suggestions for ways in which Americans outside of the government can try to influence US policy. But, also, the ways in which government officials outside the highest reaches of the executive branch can nonetheless have an impact.”