Achievements

AU celebrates the 2020 Virtual March on Washington

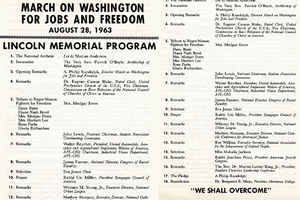

On August 28, 1963, 250,000 people participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The event was designed to amplify the concerns of Black Americans, on issues such as voting rights, police brutality, segregation, and social and economic inequity.

This year, the NAACP and partners celebrated this anniversary with virtual programming, including a keynote address by Stacey Abrams, founder of Fair Fight, and a national call to remember and fight for the aims of the original.

“The March on Washington, on August 28, 1963 was the culmination of a 25-year dream of Philip Randolph,” said Dr. Gregg Ivers, SPA professor of government and director of the school’s Julian Bond Oral History Project.

The Big Six civil rights organizations joined forces to convene the March, including Randolph, leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP; Dr. King, chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; James Farmer, founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); John Lewis, president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); and Whitney Young, executive director of the National Urban League.

In the early 1960s, the decades-long struggle for civil rights had reached a fever pitch. Student-led protests, lunch counter demonstrations, Freedom Riders, and The Birmingham Campaign drew widespread attention to the cause.

“[In 1963,] a lot of white Americans for the very first time were seeing the racist underbelly of the nation,” said Ivers. “They were seeing southern Jim Crow racism in full bore. The March motivated a lot of white Americans to get involved, or at least develop a greater sense of empathy for the plight of Black Americans.”

This national awakening was underwritten by sympathetic leadership. “In 1963, at the time of the original March, there were reasons for optimism,” said Dr. Steven Taylor, SPA associate professor of government and expert on minority politics. “Earl Warren, the chief justice, had delivered the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, John McCormick was Speaker of the House, Mike Mansfield was majority leader of the Senate, and Kennedy was president. Liberal Democrats had full control.”

Ivers echoed this assessment of hopefulness, referring to the March as “the public perception of this great moment of interracial harmony, where both celebrities and everyday people . . . came together. And it worked.”

But this harmony was not to last.

“Seventeen days later, what happened?” asked Ivers. “The bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church [in Birmingham, Ala. by the KKK], which was in part retaliation. It was a way to deflate the goodwill that was starting to build among an element of white America, and certainly mobilizing Black Americans to become more comfortable and confident in wide-scale public demonstrations.”

President Kennedy was assassinated, Reverend King was assassinated, and the movement’s momentum stalled. The same battles, to ensure voting rights, better jobs, better wages, access to education and public accommodations, and an end to police brutality, persist to this day. Though the Voting Rights Act (VRA) was passed in 1965 to prohibit discriminatory voting laws, in 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that the preclearance coverage formula, which required certain states to get approval for all changes to the electoral process, was unconstitutional. Some states immediately introduced new restrictions to voting.

“Some states are back to requiring a poll tax, in the form of state-issued IDs,” said Taylor. He voiced concerns about other attempts by the current administration to depress voter turnout, by casting suspicion on vote-by-mail initiatives and making changes to the USPS, confiscating mailboxes and sorting machines.

“Current leadership provides much less reason for optimism,” he said. “It’s not a happy time for someone who is black unless they are in a coma.”

Taylor went on to invoke a pivotal commandment from King’s speech: “[w]e cannot be satisfied so long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.”

Ivers agreed that the problems of 1963 have not been solved. “You could take the program of 1963,” he said, “air drop it into 2020, remove the dates and any identifying features, and you would have no idea when that memo was written.”

Learn more about the 2020 Virtual March on Washington at 2020march.com.