Growing up in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, the little girl would gingerly wind up her mother’s jewelry box, standing transfixed on tippy-toes as “Lara’s Theme”—named for the character in Doctor Zhivago for whom she was named—enveloped her.

The tune from David Lean’s masterful 1965 film adaptation of Boris Pasternak’s literary masterpiece is a leitmotif, weaving in and out of the story. So too has it provided the soundtrack to Lara Prescott’s own life.

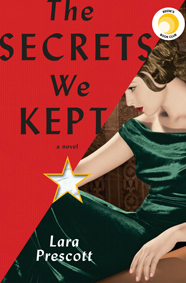

In September, her debut novel, The Secrets We Kept—which chronicles the real-life CIA plot to infiltrate Soviet Russia not with propaganda, but with Doctor Zhivago, one of the greatest love stories of the twentieth century—landed at number six on the New York Times best-seller list. Prescott, SPA/BA ’04, earned a $2 million advance for the novel, which actress Reese Witherspoon selected for her book club days before its release, propelling it to number 12 on the Amazon charts during a week that saw new offerings from Margaret Atwood and Stephen King. The Secrets We Kept is a secret no more, having been translated into 29 languages and optioned for a film.

“To get it out there into the hands of so many people has been absolutely surreal,” Prescott says, her voice trailing off, seemingly still shocked by her own meteoric rise.

And yet, this is the novel Prescott was born to write.

The daughter of bookish Russophiles, Prescott was a teenager when she first picked up the 700-page Doctor Zhivago—the story of the life and loves of physician-poet Yuri Zhivago during the turmoil of the Russian Revolution. Each subsequent reading “was like peeling away the layers of an onion,” says Prescott, who’s named for Pasternak’s doomed heroine, Lara Antipova—a character inspired by his real-life mistress.

“I felt such a strong connection with the material. It was as if the old master was reaching out to me across time and space—a candle in a window on a winter night,” she says.

Although Prescott studied political science at AU and worked as a campaign consultant in DC for about a decade, including a stint at David Axelrod’s PR firm, she had harbored dreams of being a writer since she submitted a 10-page story to Highlights magazine as a grade schooler. (“My first rejection,” she laughs.) Disenchanted with the business of politics, she enrolled at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas in 2015.

“I was working a very demanding job, and when you’re someone who has this creative part of you that’s constantly suppressed, it gets really depressing,” Prescott says from the Austin, Texas, home she shares with husband, Matt, and a menagerie of animals. “I decided it was time to return to my first love.”

Prescott credits her father with planting the seed of the idea that would grow into her MFA thesis—and eventually blossom into a book.

In 2014, he sent her a Washington Post article detailing how the CIA “weaponized” Doctor Zhivago, smuggling it behind the Iron Curtain to win Russians’ hearts and minds during the Cold War. Published in Italy in 1957, the book—for which Pasternak won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958, later declining it at the behest of Soviet authorities—was immediately banned in the USSR because of its anti-Communist sentiment. The novel was finally published in Russia in 1987 as part of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s democratic reforms. Today, Zhivago is part of Russia’s 11th grade curriculum.

“This book has great propaganda value, not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication,” reads a 1958 CIA memo, one of 130 documents declassified in 2014. “We have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country in his own language for his own people to read.”

Prescott took the stranger-than-fiction spy thriller and, well, fictionalized it.

Stylish, smart, and unabashedly feminist, The Secrets We Kept is narrated almost exclusively by women, including the CIA typing pool, which is written in first person plural. (“We came to the Agency by way of Radcliffe, Vassar, Smith. We were the first daughters of our families to earn degrees. Some of us spoke Mandarin. Some could fly planes. Some of us could handle a Colt 1873 better than John Wayne. But all we were asked when interviewed was ‘Can you type?’”)

The plot lines—which follow Irina Prozdhova, a secretary-turned-spy born to Russian immigrants; Sally Forrester, the glamorous veteran operative with a dangerous secret; and Olga Ivinskaya, Pasternak’s real-life mistress, who inspired the character of Lara in Zhivago—run parallel to one another for a few hundred pages before intersecting in heart-breaking, heart-pumping fashion.

Prescott says writing a fictional narrative within the framework of real events—the research for which took her to Paris, Moscow, and back to DC—wasn’t as tricky as it sounds. “It was freeing to be able to imagine what the lives of these people who’ve literally been redacted from history could’ve been like. There aren’t these hard and fast rules for the genre,” she explains.

As she considers ideas for her next book, Prescott says she can’t think about the success of her first one. “As a writer, you have to start fresh every time,” she says.

The New York Times reported that Prescott has begun researching the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program that paid writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and John Cheever to create “a self-portrait of America” during the Great Depression. But, in the spirit of Secrets, Prescott’s lips are sealed.

For now, she’s just happy she doesn’t have to return to politics.

“When I was graduating from the MFA program, I was looking to see what kind of campaign work I could do to get by and keep writing. Now, I’m able to just be a full-time author—it’s really unbelievable.”

Pasternak himself couldn’t have written a better ending.

Excerpt from The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott

Most of us were single, putting our career first, a choice we’d repeatedly have to tell our parents was not a political statement. Sure, they were proud when we graduated from college, but with each passing year spent making careers instead of babies, they grew increasingly confused about our state of husbandlessness and our rather odd decision to live in a city built on a swamp.

And sure, in summer, Washington’s humidity was thick as a wet blanket, the mosquitoes tiger-striped and fierce. In the morning, our curls, done up the night before, would deflate as soon as we’d step outside. And the streetcars and buses felt like saunas but smelled like rotten sponges. Apart from a cold shower, there was never a moment when one felt less than sweaty and disheveled.

Winter didn’t offer much reprieve. We’d bundle up and rush from our bus stop with our head down to avoid the winds that blew off the icy Potomac.

But in the fall, the city came alive. The trees along Connecticut Avenue looked like falling orange and red fireworks. And the temperature was lovely, no need to worry about our blouses being soaked through at the armpits. The hot dog vendors would serve fire-roasted chestnuts in small paper bags—the perfect amount for an evening walk home.

And each spring brought cherry blossoms and busloads of tourists who would walk the monuments and, not heeding the many signs, pluck the pink-and-white flowers and tuck them behind an ear or into a suit pocket.

Fall and spring in the District were times to linger, and in those moments we’d stop and sit on a bench or take a detour around the Reflecting Pool. Sure, inside the Agency’s E Street complex the fluorescent lights cast everything in a harsh glow, exaggerating the shine on our forehead and the pores on our nose. But when we’d leave for the day and the cool air would hit our bare arms, when we’d choose to take the long walk home through the Mall, it was in those moments that the city on a swap became a postcard.

But we also remember the sore fingers and the aching wrists and the endless memos and reports and dictations. We typed so much, some of us even dreamed of typing. Even years after, men we shared our beds with would remark that our fingers would sometimes twitch in our sleep. We remember looking at the clock every five minutes on Friday afternoons. We remember the paper cuts, the scratchy toilet paper, the way the lobby’s hardwood floors smelled of Murphy Oil Soap on Monday mornings and how our heels would skid across them for days after they were waxed.

We remember the one strip of windows lining the far end of SR—how they were too high to see out of, how all we could see anyway was the gray State Department building across the street, which looked exactly like our gray building. We’d speculate about their typing pool. What did they look like? What were their lives like? Did they ever look out their windows at our gray building and wonder about us?

At the time, those days felt so long and specific; but thinking back, they all blend. We can’t tell you whether the Christmas party when Walter Anderson spilled red wine all over the front of his shirt and passed out at reception with a note pinned to his lapel that read DO NOT RESUSCITATE happened in ’51 or ’55. Nor do we remember if Holly Falcon was fired because she let a visiting officer take nude photos of her in the second-floor conference room, or if she was promoted because of those very photos and fired shortly after for some other reason.

But there are other things we do remember.

If you were to come to Headquarters and see a woman in a smart green tweed suit following a man into his office or a woman wearing red heels and a matching angora sweater at reception, you might’ve assumed these women were typists or secretaries; and you would’ve been right. But you would have also been wrong. Secretary: a person entrusted with a secret. From the Latin secretus, secretrum. We all typed, but some of us did more. We spoke no word of the work we did after we covered our typewriters each day. Unlike some of the men, we could keep our secrets.

Copyright 2019 by Lara Prescott. Published by arrangement with Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.