Rarely does a human being exhibit such a stunning, Gumby-like level of elasticity that Changa Bell must stop and take notice. A certified yoga instructor, he has witnessed men and women contort themselves into spine-curling and seemingly gravity-defying poses that would send those of us who strain bending down to tie our shoelaces to the emergency room. But today, in his small carpeted studio in northern Baltimore, there's someone demonstrating such extraordinary flexibility that Bell pauses his session, grabs his phone, and aims it at one of his unlikeliest students.

Wearing baggy jeans and a long-sleeve NASA T-shirt, 18-year-old Jonathan hardly looks the part of master yogi; in fact, he's taken only a few yoga classes. But what he's currently doing leaves no doubt. He's a natural.

With his back to a wall, he clutches ropes attached to the ceiling and begins to lean forward. At the point when most people's bodies would beg for mercy, he continues a steady progression toward the ground until his legs, now virtually parallel to his mat, and his torso form close to a 90-degree angle. He looks like a capital L.

To a mere mortal, it's almost painful to watch. But Jon Jon, as he goes by, is grinning, and at least outwardly, exerting minimal effort.

"Every time [students try] this, I tell [them], 'Eventually your waist will get to the floor'—and no one believes it," Bell, 44, gushes. Then, he turns to Jon Jon: "You're incredible, and you don't even know it."

That last statement, in particular, is the one that Bell, Kogod/BSBA '07, hopes his young student will remember long after this class ends. The session is one in a partnership between Bell's nonprofit, the Black Male Yoga Initiative, and Living Classroom's Fresh Start, a job skills training program that serves out-of-school youth, ages 17 to 19, most of whom are referred by the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services.

A downward spiral of arrests and incarceration led Jonathan to drop out of high school. But since he's found his way to Fresh Start, he's earned a certification in construction flagging, hopes to get another in forklift operation, and perhaps most surprisingly, has discovered an aptitude for an ancient practice melding mind, body, and spirit, that he knew little about.

Fourteen years ago, Bell lay in a hospital bed, terrified to close his eyes because he feared they might never again open. His heart had developed a nasty habit of taking beats off. A regular drinker, occasional weed smoker, and frequent consumer of chicken wings and other fatty foods, Bell wasn't living a holistic lifestyle.

"I stayed awake for 30 or 32 hours, and then I finally had to give in," he recalls. "I said, God, if you let me wake up, I'll change my ways and be a different person. I was awakened a few hours later when the heart monitor went off, because my heart stopped. The nurse on duty came in there poking me like a turkey in the oven. When I spoke, she jumped."

True to his word, the day after Bell was released he quit happy hour and started saying no to burgers and hot dogs. He also began taking yoga classes, the beginning of a journey that he credits with saving his life—and one he believes can positively impact others as well.

For inspiration as to what to name their second born, Thomas and Lillian Bell looked to Nigeria. Changa means "strong as iron" in the tongue of the Yoruba people. Both educators, the Bells raised their two sons and daughter in a working-class African American neighborhood near Morgan State University in Baltimore. Thomas routinely practiced yoga, but his sons paid little attention. Changa was fiercely independent and decreed that college was not necessary for him to achieve his dream of being a filmmaker.

During his 20s, however, Bell discovered that stardom was elusive. He worked as a production coordinator on some big-budget movies like Michael Collins and Turbulence (and even landed a small on-screen role in The Omen), but felt pigeonholed in part because of his age and race.

"The only kind of opportunities we were being given were music videos," he says of young African American filmmakers in New York. "I was trying to tell powerful humanist stories, but [the establishment] said those weren't my stories to tell."

At the age of 30, Bell enrolled at AU, where he earned a degree in international business and met Devonna, a School of International Service student who would become his wife, business partner, and the mother of five of his six kids (he had one child before they met). It was around this time that he began noticing an alarming irregularity with his heart.

"I developed some sort of arrhythmia to the point where not only was it not beating in rhythm; suddenly it went off cadence and would actually stop beating for 10 or 15 seconds," he says. "Of course, that felt like an eternity. It's scary as hell. I might pretend to cough and start pounding my chest to wake it up."

Doctors couldn't pinpoint the cause of the problem. A medical technician told Bell that a sonogram of his heart looked "beautiful." Bell left the hospital confused but grateful for a second chance. He sought out his father, who gave him a book on yoga.

While many people see yoga simply as a workout regimen for yuppies, others regard it as a lifestyle. Bell became enamored with the practice's physical benefits, but also its tenets of mindfulness. His new path has worked. Even though he still struggles a bit with his diet (he tries to follow vegan principles, but he's what his children have dubbed a "flexitarian"), his heart hasn't skipped a beat since his scare more than a decade ago.

In 2014 Bell's transformation became complete when he left his job at Georgetown University to run Sunlight and Yoga Holistic Wellness Center, where he practices the Patanjali and Sivananda styles, which many may not be familiar with. He's switched to a business model in which he teaches aspiring teachers the "metaphysical and ephemeral" aspects of yoga.

"Yoga reverses many ailments, and if it doesn't directly detoxify the body to health, a person will develop a keen awareness of their body to the point where they may catch a minor health challenge before it is significant," Bell says. "It's like an ongoing diagnostics test for the body. When I speak of yoga, I am speaking of practicing and living all eight limbs, not the calisthenics or heated versions offered in major studios. That is a commercial application, a specific type of business model. To me, yoga is a journey inward of self-realization."

Last year Bell received a BMe Leader Award. He used some of the monetary prize to start the Black Male Yoga Initiative to introduce men of color, ages 16 to 65, to the practice as a method for making positive and healthy change in themselves and their communities. Among his first partners was Fresh Start, a program administered by Living Classrooms, a Baltimore nonprofit dedicated to education and job training.

"[We] saw the need to provide additional services for our young men to aid with their emotional wellness," says Cheryl Riviere, Fresh Start's program director. "Our young men [come] from high stress environments, and providing them with another option to cope with their daily lives was needed."

A slender young man with a wide smile, Jonathan is "high energy all the time," as one of his Fresh Start teachers puts it. But in Bell's yoga class, he's attentive, calm, and engaged.

"I feel loose," he says of his time on the yoga mat. "I think it helps your mind. It clears everything out, and I feel more focused."

Brian Furr can relate. An entrepreneur who also teaches business organization administration technology at Fresh Start, he knew next to nothing about yoga. For the 27-year-old former high school track athlete, the thought of being a novice in a room with seasoned students—most of them white women—was intimidating. But after taking a few classes with Bell through the Black Male Yoga Initiative, he's become more comfortable and confident, a transformation

he sees in his own students.

"A lot of these guys come from backgrounds where they aren't praised for who they are," Furr says. "It's always like, you gotta change. What I've found is, a lot of times they act out because they just want to be who they are. This is a way for [Jonathan] to be naturally good at something, and it doesn't have to be overly masculine, like basketball or football, where it's almost combat. He's naturally good at it, and he gets praised for it, and that positive reinforcement I think extends into other aspects of his life."

Riviere cites examples of young men backing away from drugs after working with Bell, and others using mindfulness techniques in their neighborhoods to extricate them from stressful situations.

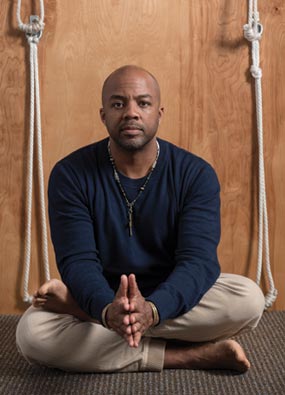

Bell strives to create a safe space where his students can leave their troubles behind. At the beginning of the class, he plays a soft mix of jazz and hip-hop, opens the sliding glass door to allow sunlight and fresh air to stream in, and asks each of his students how they're feeling. With his shaved head, days-old scruffy beard, and a faded gray Baltimore Colts T-shirt that's oh-so-Charm City, he exudes a nonthreatening, caring persona.

"I don't judge them," he says. "I don't say you should adopt mindfulness and yoga to improve your life. I try to do what my dad did: I try to be a model. I'm embodying the behavior and practices, and I do my best to engage them in it and get them interested."

At least on this hot Friday in May, he's succeeding. Toward the end of the class he distributes small pillows for people to place over their eyes as they lie on their backs in Shavasana, or corpse pose.

"You want to let your mind relax and do what we call following your breath home," he says. "Become aware of the gentle rise and fall of your breath in the body. Make a mental check-in with your emotions and your thoughts. Add a descriptor to that presence—maybe it's peace, maybe it's calm. Add that quietly to your mind so you can carry that into your day and hopefully tomorrow."

He pauses to let the meaning of his words sink into his students' young minds. The music is off now; the only sounds are birds chirping so melodically they almost sound fake.

"Namaste," Bell says, concluding the class. "Namaste means 'the divine in me recognizes the divine in you.' May you leave here with a deeper connection to your highest being. Namaste."

Lying on his mat, Jonathan raises his head ever so slightly, then subtly parts his lips. Namaste, he mouths quietly to himself.