¡Hágase contar! Ako mapabilang. រប់. Be counted.

Everywhere they looked this summer, residents of Long Beach, California, were reminded—in Spanish, Tagalog, Khmer, and English—that their city was counting on them.

“We tried to put it in front of peoples’ faces as many times as we could,” says Julian Cernuda, 2020 census project manager. More exposure leads to more responses, so “Be Counted, Long Beach” was plastered everywhere in the coastal city of 460,000: billboards, sidewalks, buses, tote bags and T-shirts, Facebook, and even COVID-19 testing centers.

Outreach grew more complicated in a touchless world, but Cernuda, SPExS/WSP ’12, was already ahead of the game when the coronavirus hit. By summer 2019, his team had canvased its hard-to-count neighborhoods and low visibility housing units—like converted garages and granny units—to provide the US Census Bureau with an updated address file. They also met with representatives from 45 local organizations to brainstorm how to educate residents about the decennial questionnaire and motivate them to complete it.

The census determines not only the apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives but also the allocation of federal funds—an annual tax dollar pie of $1.5 trillion—for Medicaid, infrastructure, food programs, and more. An incomplete count leads to lost cash: up to $20,000 per uncounted Long Beacher over the next decade, Cernuda says.

In 2010, more than two-thirds of American households responded online, by mail, and over the phone, and more than 550,000 enumerators went door-to-door to nudge the stragglers. That undertaking is challenge enough in a “normal” year. Throw a pandemic into the mix and it becomes much more likely that people—historically, people of color—will fall through the cracks. The Urban Institute estimated in 2019, even before COVID-19, that Black and Latinx Americans could be undercounted by as much as 3.5 percent.

Navigating this enumeration period also meant confronting constant logistical and legal roadblocks. Last summer, the US Supreme Court blocked a citizenship question from appearing on the questionnaire. And in September, federal courts prevented the Trump administration from excluding undocumented immigrants from the census and from ending the count a month ahead of its October 31 deadline. Another ruling by the US Supreme Court then stopped the count on October 13.

Mixed messages can cause confusion, fear, and distrust. Natasha Quiroga, WCL/JD ’07, SIS/MA ’07, sought to combat all three. The senior counsel for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law spent much of 2020 running a census protection hotline staffed by 200 pro bono attorneys.

“Every day something new is happening,” Quiroga said in late August. “We’ve had a lot of people report potential scams or ask, ‘Can my undocumented neighbors still fill out the census form?’ It feels good to be able to reassure folks and to make them feel like they’re counted.”

It was an important step toward ensuring accuracy and fairness in a process that comes once every 10 years—but impacts our lives every day.

NO REPRESENTATION WITHOUT ENUMERATION

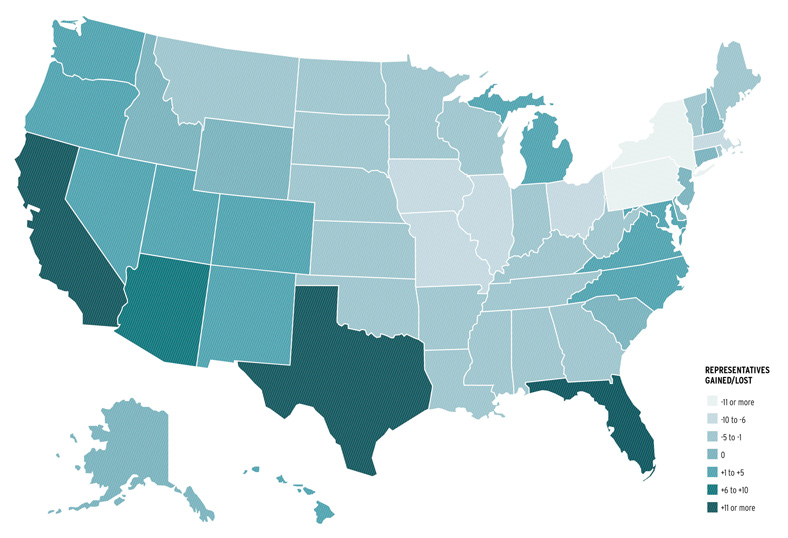

- The Apportionment Act of 1911 expanded the House of Representatives to 433 members with room to grow by two—one each for new states Arizona and New Mexico. The law took effect in 1913, capping the lower chamber of Congress at 435. Take a (House) seat and learn how the last 10 censuses have shifted state representation.

- Along with Delaware, Wyoming is the only other state whose representation has held steady at one since 1913. (Idaho and New Hampshire have remained at two.)

- Nevada quadrupled its delegation to four in just four census cycles.

- California jumped eight seats after the 1960 census—the largest single-cycle gain in the last century.

- After achieving statehood in 1959, Hawaii and Alaska each received a representative, growing the House to 437 seats until 1963, when it shrunk back to 435.

- Alaska, which has one representative, is the largest congressional district by land area in the US.

- North and South Dakota’s delegations have shrunk by 67 percent since 1913, going from three representatives to one.

- Missouri had the sixth-most representatives in 1913. Today, it has the nation’s 18th largest delegation.

- Michigan is the only state to gain and lose at least five representatives since 1913.

- New York’s 13th District is the nation’s smallest at 10.2 square miles.

- Pennsylvania has shed seats in nine straight censuses after reaching a peak of 36 in 1913-23. It is projected to lose one of its 18 remaining seats this cycle.

- Virginia fielded the largest House delegation until 1813. New York (1813-1973) and California (1973-present)

- Florida’s delegation grew from 4 to 27 representatives in just nine census cycles.

- Texas is projected to gain up to three congressional seats following 2020 census reapportionment. It would be the Lone Star State’s eighth consecutive cycle with a gain.

MAKING SENSE OF THE CENSUS

- In 1913, there were roughly 210,000 constituents per representative. Today, there are about 750,000.

- By federal law, individual census records are not publicly available until 72 years after they are collected.

- In 2010, about 565,000 enumerators went door-to-door to finish the count—up from 70,000 a century earlier.

- The equal proportions method—which gives one seat to each state and uses a mathematical formula to divide the remaining 385—has been used since 1940.

- Native Americans were not recognized by the census until 1840 and enumeration on reservations did not occur until 1900.

- Heading into the 2020 election, state lawmakers were responsible for congressional and state legislative redistricting in 35 and 36 states, respectively.

- Twelve states’ delegations have been cut by at least 50 percent since 1913.

- The 2010 census finished $1.6 billion under budget—largely because 72 percent of households completedthe questionnaire on their own.

- Enslaved people were counted as three-fifths of a human being in the first eight censuses.

- More than 1 million members of the armed forces, other federal employees, and their dependentsliving abroad were included in the 2010 apportionment counts.

- Only once has reapportionment failed to occur: after the 1920 census, when rural district representatives, fearful of America’s urban shift, delayed legislation.